|

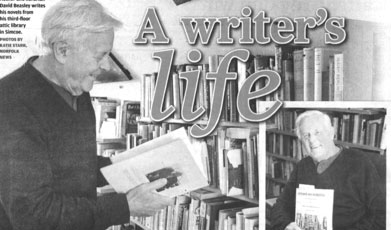

Episodes Volumes 1 and 2 Author and librarian David Beasley writes his novels

David Beasley shares tales from a life well-lived in Episodes and Vignettes: an Autobiography David Beasley has always drawn from real life in his written works, but his latest book, Episodes and Vignettes: an Autobiography, is his most personal yet. "Being a writer, you use the material that's at hand," the 83-year-old author of Sarah's Journey, his best-known novel, says from his attic library overlooking Norfolk Street in Simcoe. Born and raised in Hamilton, he left for Europe after graduating from McMaster University and stayed abroad for five years, bouncing around London, Paris and Ibiza before settling in Vienna, where he taught English. He later spent 35 years as a research librarian in Manhattan. When he had finished reading those books, Beasley started writing his own. "It must have been that knock on my head from the car, because from then on I started writing and I haven't stopped," he says. WILLIAM LEO COAKLEY, Librarian and poet ——————————————————————————— A friend critiqued the Autobiography. I excerpt phrases from her email which give her viewpoint. I reply giving my intentions in writing the memoir in hopes they may inform the would-be reader. Your books are so heavy (they weigh all of one and a half kilos each!) I can hardly lift them! ...the text itself is so wide it's rather like having a side seat at Wimbledon - eyes left, eyes right, left, middle, right, left, middle, right. . . . the whole book is so detailed, with so many names, of friends and relations (like Rabbit!), teachers and towns and streets and teams and rules of games, all quite unfamiliar and incomprehensible to the likes of me!... You tell us, the readers, what's happening on stage without actually making us see it. ....Who are you writing for?? I think you have to decide. And if it's for a general readership, you must select and only use the interesting bits. To put everything in pleases no-one and is, in fact, simply boring.... Style. Your sentences, like your whole book, are too long. You are not writing a 19th century novel! You like subordinate clauses, but everything becomes more immediate, more interesting, if you chop it up. ... Too many of your sentences have an anti-climactic ending. ...Letters. These are personal and of importance to you and whoever wrote them or received them, but honestly, as they are, in their entirety, are not of interest to the uninvolved reader. Why not select a few salient bits which will carry the action or the interest forward without telling us everything, especially the greetings and signing-offs! The same, I feel, apples to your sexual exploits (unless, as above, you can make them funny or really significant). They're personal and are slightly embarrassing for the general public. We feel like Peeping Toms! My reply: Thanks for the frank assessment. I was not so much writing a book as putting one together. Luckily I did just 100 copies. It was an experiment. My aim was to capture things as they were and to not edit the actual journal entries or letters. I felt that they represented an attitude, a moment in time, a tracing of a life in all its faults, stupidities, misadventures, struggles, even to the extent of embarrassing myself. My comments on the events recorded in journals and letters are just that, not done with a novelist’s technique. If readers don’t like the writing they can close the book. Some have enjoyed my descriptions of Europe, etc. Anyway I wrote for myself, especially in this case. Usually autobiographies are shaped to advance the character and events of the person writing it. They can be written in several drafts with an expert editor. I eschew all that. You have not read my novels and much of my nonfiction, other than the two biographies on art which I sent you. Those are written the way you say they should be, they are crafted but not programmed. They are created. The autobiography is different. In art terms, think of collages, although even they are more determined than the autobiography. I suppose time will tell whether the volumes have any value. . . . If I were writing an autobiography, creating it as I went along, that is like a novel, I would of course not have mentioned all those names —I was writing a record. If boring to the reader, I am sorry but so be it. If not boring but an interesting kaleidoscope of a life in flight, all the better. One fellow in Simcoe did refer to the book as archival—so he has your viewpoint. Others are taking it in as amazing for memory and fascinating in detail of impressions in Europe and elsewhere. I was surprised when they read the complete two volumes. They are about a time, and I am but a mere actor in that time; although the details are from my life, those details are a reflection of that time as seen through me. As for style, it changes according to the subject or genre. For instance, my detective novels reflect your taste for short sentences. I chose the size of the book to avoid having to put out three or four volumes. I included Viola's letters because she writes well, with emotion, covers our life together and portrays the difficulties of an immigrant family in a society totally different from the one they grew up in and very foreign to them. Perhaps you can read passages at random. That may be the best way. Thanks again for your comments—illuminating as always. From the above the reader may expect me to recast the book. One reader suggested that I just select the best letters and use them. Perhaps I can make an engaging autobiography out of the two books. But it is not as if I did not have the ms read before publishing it. The woman who read it read widely and with discrimination. She advised me not to change anything, except perhaps to cut out some material on the labour union activities. I repeat that it is an experiment, which is true of all writing really. Whatever the reader's tastes and expectations I intend to entertain and educate in my writings. Recently I read passages to a Rotary Club meeting. Some members roared with laughter while others seemed struck dumb—either with surprise or appreciation but not boredom. I should add that I considered the detail important. I wrote as much for the future as for the present.

|

|||

|

|||